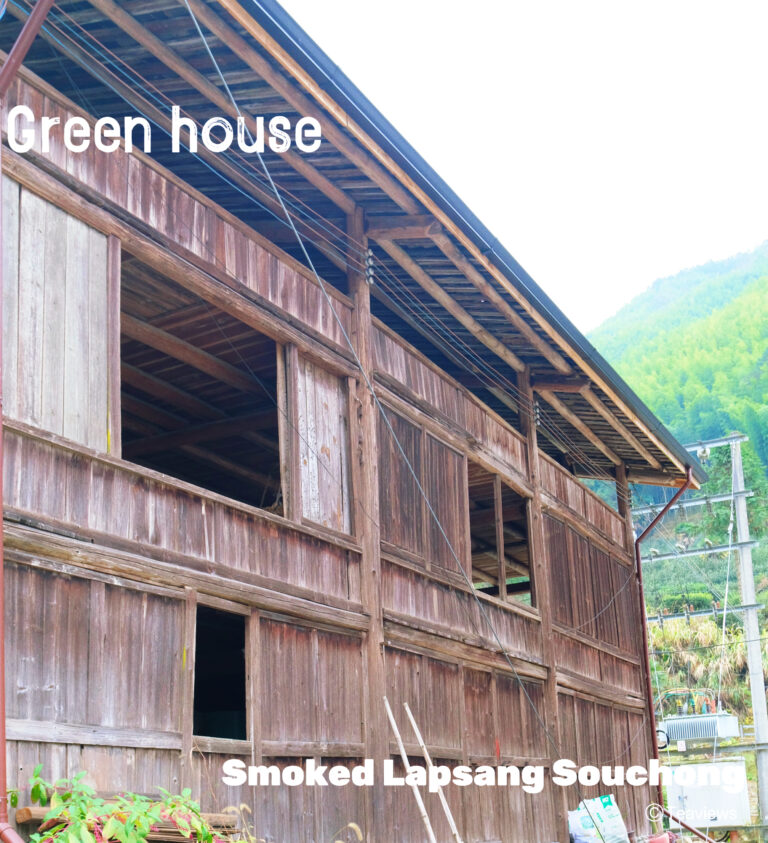

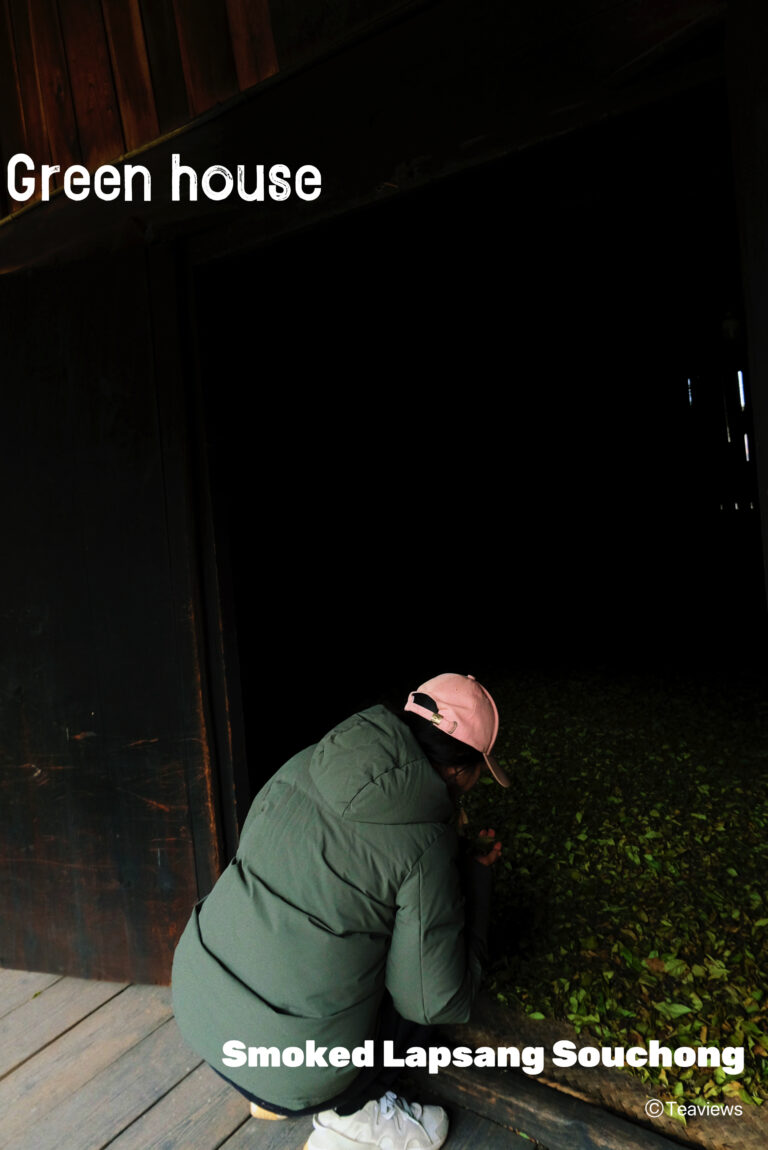

In Tongmu Village, those stilt houses with green tiles and blackened wooden walls are revered by tea folks as “qinglou”(green house). Far from being places of vice, they are the sacred shrines of the smoking process for Lapsang Souchong. The building has three floors. On the ground floor, century-old Masson pine is burned. As the pine resin drips into the fire, it crackles and bursts into star-like sparks. On the middle floor, bamboo mats are arranged, where the tea leaves quietly absorb the pine smoke. On the top floor, the dried tea is stored, and the lingering heat slowly seeps the pine fragrance into the very essence of the tea. During the tea-making season, the “qinglou” hosts an ancient and grand ceremony, condensing the soul of Chinese tea into a poetic scene filled with the aroma of smoke and fire.

“During the tea-picking and tea-making seasons, every household is in a flurry of activity. At night, lights shine brightly everywhere. The tea masters are busy crafting tea, the pickers are busy plucking the leaves, and the women in the family are busy cooking for the workers and handling other chores,” Wen Changjing said with a smile. “Our tea-making season lasts around 60 days, usually starting in early April and wrapping up at the end of June each year. We often joke that compared with rock tea production, our tea factory starts earlier and finishes later, but we get to enjoy the first spring tea earlier.”

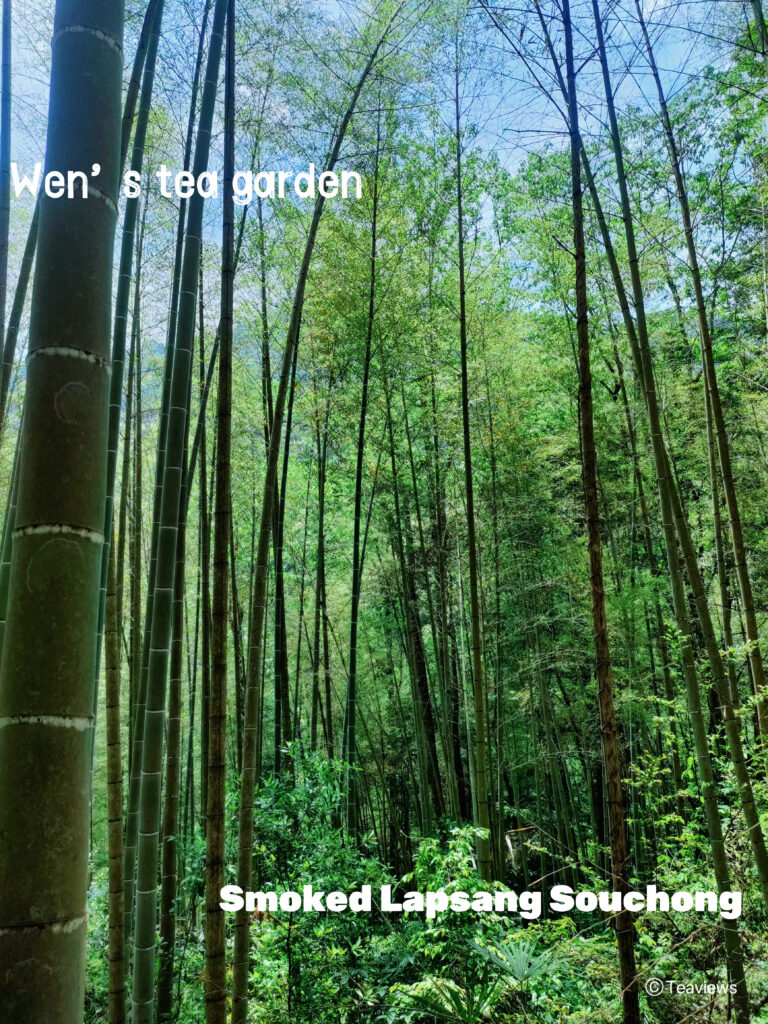

Around the first rain of the Qingming Festival, the villagers start picking the single-bud Jin Junmei in the mountains. Around the Grain Rain in April, the mountain dwellers pick the “one bud and two leaves” (小赤甘) in the morning dew. After the Beginning of Summer, they begin to pick “one bud and three leaves” to make smoked Lapsang Souchong. Making tea on schedule and according to the weather is a long-held pact between generations and nature. The tea leaves wither on bamboo trays, gradually losing their emerald green luster like jade losing its sheen. At night, pine firewood is lit in the stove of the “qinglou”. The tea farmers, relying on their experience, control the fire—if it’s too fierce, the smoke will be harsh; if it’s too gentle, the aroma will be faint. In the swirling smoke, the tea leaves mingle with the pine fragrance for seven days, until the dark, glossy tea strips are dusted with amber-colored fuzz, and the sweet scent of longan wafts out from the wooden window lattice into the starry night sky.

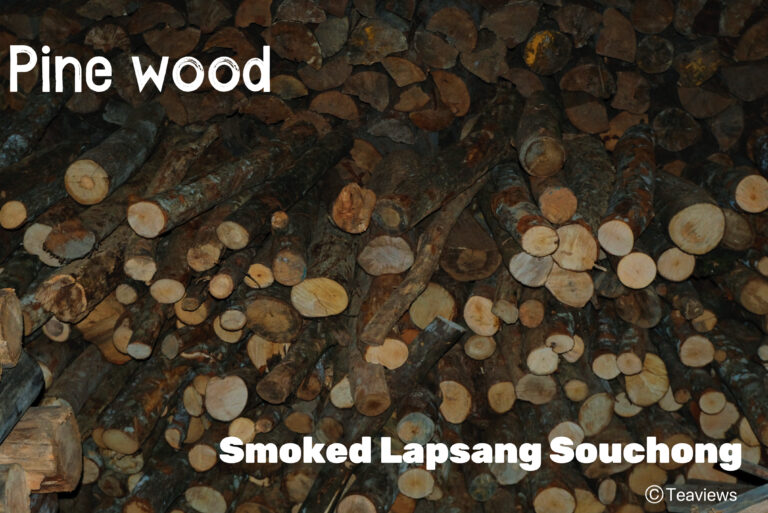

For the traditional smoking process, the tea must soak up three rounds of smoke in the “qinglou”, and it has to be Masson pine. In the first round, during withering, the fresh leaves absorb the smoke as the pine smoke is drawn into the leaves through the nutrient transport in the tea stalks and seeps deep within. In the second round, during drying, the tea takes in more smoke, allowing the pine fragrance to fully permeate. In the third round, during re-roasting, another bout of smoke makes the pine fragrance blend even more harmoniously with the tea. Due to the control of pine wood in the nature reserve in the past two years, the Lapsang Souchong that can fully preserve the traditional process has become even more precious. Only with top-notch raw materials, excellent pine wood, superb craftsmanship, and proper storage can a truly authentic cup of Lapsang Souchong be created.

Now, there are only about a dozen traditional “qinglou” remaining in Tongmu Village. The old tea masters say, “The pine smoke aroma is the very soul of Tongmu Guan. One sip of the tea smoked in the ‘qinglou’ and you can envision the misty expanse of Wuyi Mountain.”

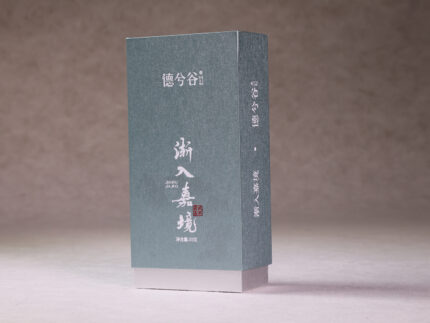

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

I like Lapsang Souchong, but I’ve never known about Tongmu before. It seems to be a really mysterious and wonderful place. And the monkeys there are so cute. 💕