Last year, I met Derek, an American who was learning about tea in Wuyi Mountain. He journeyed all the way from Brooklyn to Anup ji in India, then to Chiang Mai in Thailand, and finally came to Wuyi Mountain in China to live and study. He is a senior yoga instructor and singing bowl healing therapist, and now he has become a die – hard enthusiast of Chinese tea.

We hit it off as soon as we met, so naturally, I asked him why he was here. He said that his affinity with Chinese tea actually began in Beijing. After each yoga session or singing bowl therapy, he liked to replenish his energy with various natural beverages. He had explored a wide range of drinks, from herbal, vegetable, and fruit concoctions to tea. “However, my initial fondness was mainly due to my body’s instincts. I was drawn to their natural aroma, pure taste, and the pleasant physical sensations they brought,” he said. “That was until I happened to meet my first tea teacher, Teacher Liu, during my trip to Beijing.”

“I’ve always remembered that scene,” Derek said.

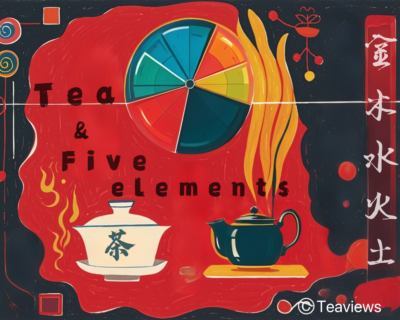

In a tucked-away Beijing *hutong*, Master Liu pours boiling water into a Yixing clay pot, his hands moving with the unhurried precision of a calligrapher. “Tea is not a drink,” he says, eyes crinkling. “It’s a conversation between heaven, earth, and the five elements.” The pot, shaped like a gnarled tree trunk, releases the scent of aged pu-erh—earthy, primal, as if the very soil of Yunnan had folded itself into the leaves. Outside, the 21st century buzzes with delivery scooters and WeChat pings. Inside, time bends to the rhythm of“Wu Xing”(五行), China’s ancient Five Elements philosophy, where every sip is an act of cosmic diplomacy.

So, this is not merely a tale of learning about tea, but also one of an individual’s quest in China for the Five Elements, that legendary and miraculous energy.

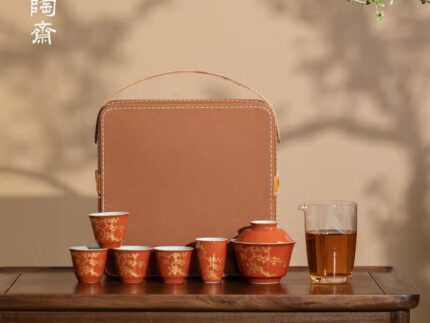

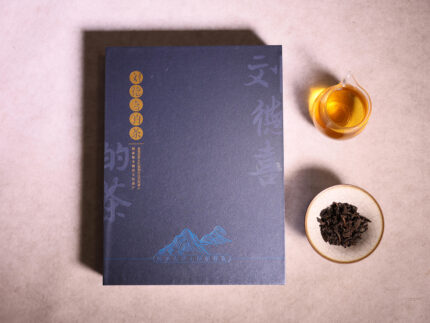

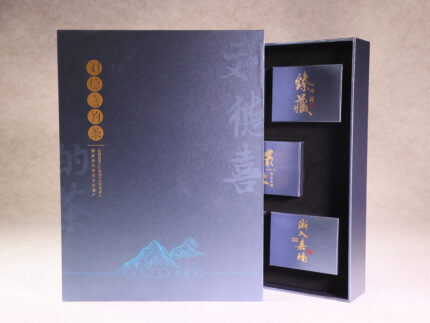

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page